Chris Jones

Entertainment Editor

Chris Jones, from Washington, Illinois, is the Mail Entertainment Editor covering Movies, Television, Books, and Music topics. He is the owner, writer, and editor of Overly Honest Reviews.

What happens to make-believe when the safeguards put in place to maintain it suddenly stop working? WESTWORLD begins with luxury and the idea that anything is possible, and then steadily takes each of those things away, to the point where the very idea of being in control starts to seem like an illusion. Michael Crichton’s first time directing a film doesn’t spend any time preparing the audience. Delos is shown as a place for rich people to play, a place where harm has supposedly been done away with. Visitors can drink, kill, have sex, boss people around, or act out fantasies without any trouble, as the robot ‘hosts’ are made to take the harm and just reset. The offer is deliberately appealing, and Crichton knows the film will only work if people first accept the attraction. WESTWORLD doesn’t warn you right away; it invites you to come in.

What does redemption cost when the person you’d need to be forgiven by has every reason not to forgive you? UNDERCARD isn’t interested in handing out simple answers, and it’s this refusal which, in the end, gives the film its strongest moments. The basic idea is one we’ve seen before, with a former boxing champion, now a trainer, and in recovery from alcoholism, goes back into her grown-up son’s life after time away. He’s skilled, but doesn’t apply himself, and is with people who want to make something of his ability, people who’ll take advantage. She thinks this is one final chance, not just to make someone a fighter, but to fix what she broke. But UNDERCARD isn’t, first and foremost, a sports story about someone making a comeback. It’s a story about facing up to what you’ve done, which just happens to be set in and around a boxing gym. This is how the film keeps itself from being a one-dimensional copy of a redemption story.

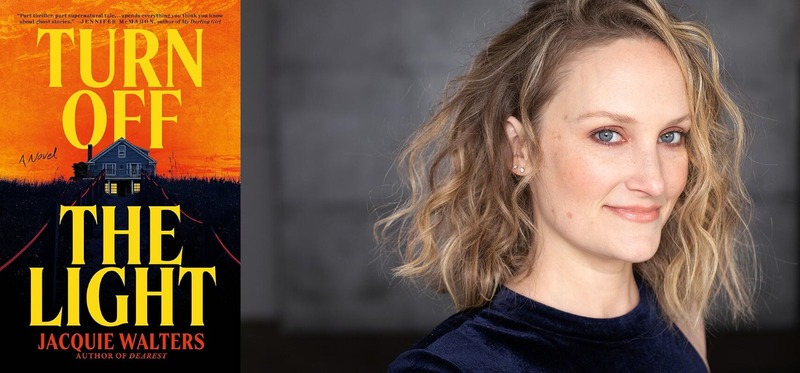

What happens when a house doesn’t only have memories, but instead takes part in them? TURN OFF THE LIGHT is built around that idea, and then slowly but surely turns the screws on you until the very walls seem to be in on it. Jacquie Walters is back after her first novel, with something much more ambitious in terms of how it’s put together. This isn’t a typical haunted-house story told across time; it’s a meeting of generations and a look at fear, belief, and how women survive. In the 1600s, on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, Edith is a healer, someone her community depends on, but also someone they worry about. In the present, Claire returns to the house where she grew up to look after her father as his health declines, bringing her little girl along, and the place she once called home seems strangely aware of the situation. The link between the two women is the land the house stands on, but Walters wants to explore something beyond where things happen: she’s thinking about what people leave behind.

When a movie won’t explain itself, not in an attempt to be mysterious, but because it simply has too much going on, then what happens? THE VISITOR begins as if it assumes we already know how their world works, though those rules seem to be made up as it goes along. The film cares less about a focused story than about keeping us disoriented, and this dedication is at once its best quality and its biggest problem.

What happens when an action movie stops trying to make sense? KNOCK OFF decides to dive into the shallow end and challenge you to either give in to the craziness or just scratch your head and wonder what you’re watching, This isn’t a film that wants to let anyone get comfortable and acclimate to its world; it goes quickly, is loud, and piles on the absurdity with the confidence of a director who figures you’ll keep up or be left behind.

What happens when being loyal to your job begins to feel personal? That’s an interesting focus in AMERICAN YAKUZA. This movie appears to be a standard undercover police story, yet it frequently returns to a more complex emotional problem beneath the shooting. It’s a film more concerned with the gradual loss of being sure of things than with surprise or size, though it isn’t always able, or determined enough, to work out that idea fully.

There’s a specific kind of project that only exists because someone once made a joke about it, and then decades later decided to cash that joke in. MEL BROOKS’ SPACEBALLS: THE ANIMATED SERIES is exactly that. It’s not really a sequel anyone demanded (we’ll get that in 2027!), it isn’t an expansion of the lore that anyone needed, and it isn’t particularly interested in pretending otherwise. From the first moments on screen, the series feels less like a continuation of SPACEBALLS and more like a prolonged shrug that says, “Yeah, fine, you asked for more, here’s more.” That self-awareness ends up being both the show’s saving grace and I’d say what holds it back, but it knew exactly what it was.

What happens when misery won’t leave you, and the only thing the departed can grasp is revenge? GARDEN OF LOVE doesn’t approach this question with benevolence. It puts it in focus, then waits before ripping people apart. Olaf Ittenbach’s 2003 splatter film has long occupied a strange place among fans of extreme horror; some find it to be too much, while others accept it as operatic violence. Now, with Unearthed Films’ Blu-ray, it seems less like somebody letting themselves go, and more like a director deliberately getting better at what he does.

What happens when a society comes to think of crime not as something to be solved, but as something to be manipulated, a number to change? That’s the quiet question at the heart of CENSOR ADDICTION, and the film never lets it go. Michael Matteo Rossi’s near-future dystopian thriller, set in 2030, presents a world where a very powerful medical company deliberately causes trouble to profit, and then sells the idea of controlling things to the people. The idea isn’t presented delicately, and that’s absolutely intended.

What does it mean to try and find where you fit in your body, when the world is so keen to put you into a box, and when that box itself is being questioned? THE TALLEST DWARF is a documentary that begins with the filmmaker’s own doubts and doesn’t turn those doubts into something to be looked at. Julie Forrest Wyman doesn’t approach this topic as someone who has all of the answers, or as a director hoping for a straightforward idea to emerge from it. Rather, the film works through a series of questions and shows how identity can be formed, rejected, put off, or quietly changed by the medical profession, by what people generally believe, and even by kindness that says nothing.

What does it mean to live in a world that has already decided you’re not important? THE KEY is based around individuals who’ve managed to vanish, not by choice, but as the easiest way to get by in life. Paul G. Sportiello’s first feature film isn’t about showing off poverty or on the outside to make a point about morality. Rather, it depicts invisibility as something people learn, something handed down between those who come to realize that not being noticed is, at times, safer than being seen.

How big does a monster story have to become before it overcomes the individuals in their immediate vicinity? The second season of Monarch: Legacy of Monsters arrives with a very definite goal: to be bigger, to go further, and to at last prove its right to be within the Monsterverse, not just adjacent to it. The first season was often a fairly down-to-earth drama about people who happened to be near these major events; the second season aims for direct impact. The result is more self-assured, more ambitious in its visuals, and sometimes a little bit awkward, yet also more satisfying when it remembers what made the show good in the first place.

What does it mean for the most well-known songwriter on earth to suddenly find himself without a band, without any support, and without any certainty that people still want to hear what he is doing? MAN ON THE RUN doesn’t attempt to cover The Beatles' story again, nor should it; we have multiple documentaries that have told that story. Here, we’re posed a tougher question: what happens when a legend has to demonstrate his worth from the beginning?

What do you do when the world around you feels like the very thing you’re attempting to get away from? TONY ODYSSEY begins with that problem embedded in its core; it’s rooted in the quite ordinary disappointment of a person, before the movie breaks apart, twists, and ultimately doesn’t bother to be polite or even make sense (and doesn’t need to). From the first scenes, Thales Banzai’s first film shows that this isn’t a story that wants your comfort, or to make things clear, or even to reassure you. It’s a film about being used up from deep inside, about the harm of not moving forward, and about the idea that, perhaps, past the rules, there’s some way to get out.

What happens when trying to be relevant means facing up to those you’ve let down? K-POPS! presents itself as bright, musical, though its real heart is more subdued than you’d think. With the energy of a K-pop contest and the fun of a stranger-in-a-strange-land idea, it is a tale of a man who confused what he wanted to do with what his purpose was, and is now at last made to deal with the difference. Anderson .Paak’s first time directing doesn’t attempt to change the genre.